The photographer has been making iconic American images for nearly 50 years.

Save this article to read it later.

Find this story in your accountsSaved for Latersection.

Dawoud Beys workis both a documentation and an excavation.

In a boy at a bus stop, he sees a Rembrandt painting.

Where one sees an ocean, he sees the people who drowned in route to freedom.

His visual poetics show the America we want to forget.

(No matter where his work pulls him, he always follows the water.

Proving that water is a body too.)

Its been nearly 50 years since Bey started making work.

He was a clear visualization to me of Harlems past in the contemporary moment.

He could have been standing there in 1920 or 1930 or 1940.

I got to the end of the block.

So I turned around and started walking back.

I just fixed my gaze on him and I said, Hi.

I really love the way you look.

Do you mind if I make a picture of you?

I wanted to focus on the African American community within the landscape of the city.

Look how he styles that Kangol in his own particular way.

Its a very conscious set of choices that hes made in his self-presentation.

At this point, I would basically do anything.

This man just ignored me, but he knew I was there.

He was the lone figure in the triangle amongst the light and dark and shadows.

One of them was track, one of them was dance.

She was really active in school.

This is probably the end of the school year.

I wanted to affirm that:Oh, I love those medals!

Im so proud of you.

I had started making black-and-white Polaroids on Cambridge Place between Fulton and Gates in Clinton Hill.

I used to see Biggie (Notorious B.I.G.)

because we worked on the same corner every day.

He had a hard-core persona, so I never approached him to photograph him.

But I knew him and he knew me.

I made them in Brooklyn so I wanted folks in Brooklyn to see themselves.

And that continued in my work.

None of those people in my Syracuse photographs ever saw their photos.

I started to become uncomfortable with that.

This photograph was initially inspired by my encounter with Rembrandt paintings.

It was the beginning of a new way of making and thinking about my work.

There are fundamental problematics in the imbalance in the relationship between subjects and photographers.

But this way, theyre able to both confirm and affirm the way that I was seeing them.

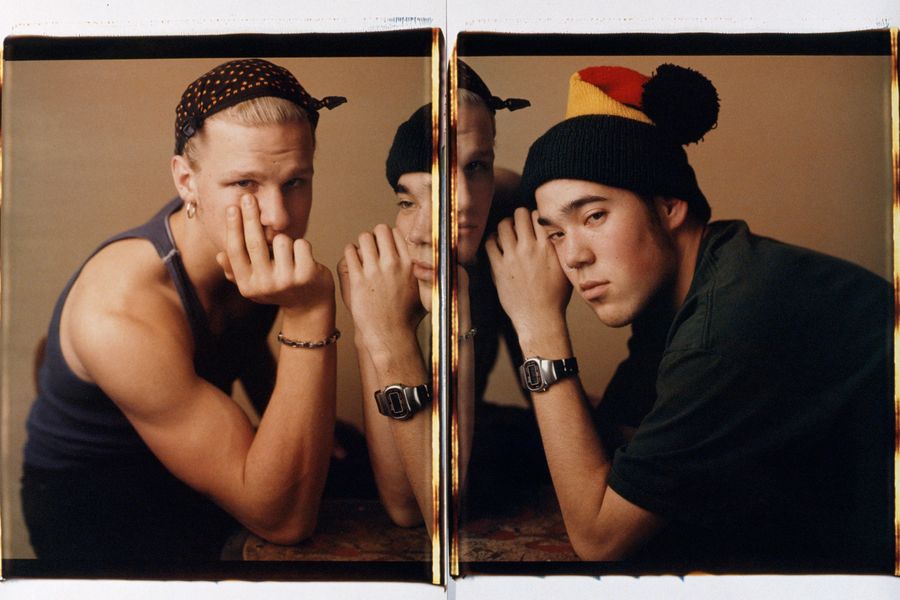

I wanted to eliminate the narrative of place.

And to focus more resolutely on the subject.

They brought home a book calledThe Movement.

Thats when I decided to go to Birmingham.

My series The Birmingham Project was a real conceptual shift in my work.

This is the first of what turned into a research-based project.

The four girls had a kind of mystic and abstract presence.

I knew that I wanted to make work that gave them a more tangible, palpable presence.

What does an 11-year-old girl look like?

Not four little girls as a group.

One woman subject said, You know, youre making me remember things.

They were all haunted by the memory of that moment.

Some of the sitters knew some of the girls.

Some of them remembered feeling the blast.

Birmingham was once called Bombingham for all the bombs that would detonate.

When Caela walked in, she was so small, and my heart just caught.

And then, when she got in front of the camera, her whole disposition changed.

And she was fully present.

That intensity of focus and engagement.

This was the moment in this project whenI stopped working and I went home to regroup.

Its 50 miles across Lake Erie to get to Ontario, to get to freedom.

Many of the locations of the route are unknown.

This was the last photograph that I took for this series.

It was almost like I could look up and see them.

Those that crossed here.

And the water is also how Black people were brought to this country.

Water is an important part of the Black experience, and it holds memory, even when we dont.

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism.

*An earlier version of this piece incorrectly stated that the Hilary and Taro image was made in Chicago.

It was in fact made in Boston.