His new memoir is both a coming-of-age story and an evolutionary step for Asian American literature.

Save this article to read it later.

Find this story in your accountsSaved for Latersection.

Hua Hsu entered the store with a box full of books.

He was told the haul would fetch him $70 in cash or $120 in store credit.

Hsu and Ken form a kind of spectrum of Asian assimilation.

Yet their race can often feel incidental to the story.

Hsu and Ken drive around in their cars.

They smoke a lot of cigarettes.

They argue about music and films.

None of this should feel extraordinary, yet it does.

They are both Asian and not, equally embodying the American side of that hyphenated ledger.

It is a characteristically modest claim that also feels like an evolutionary step for identity-inflected literature.

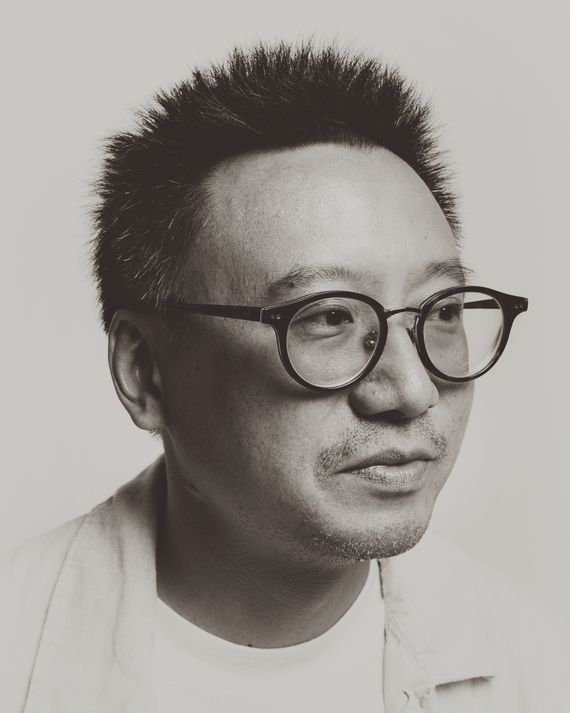

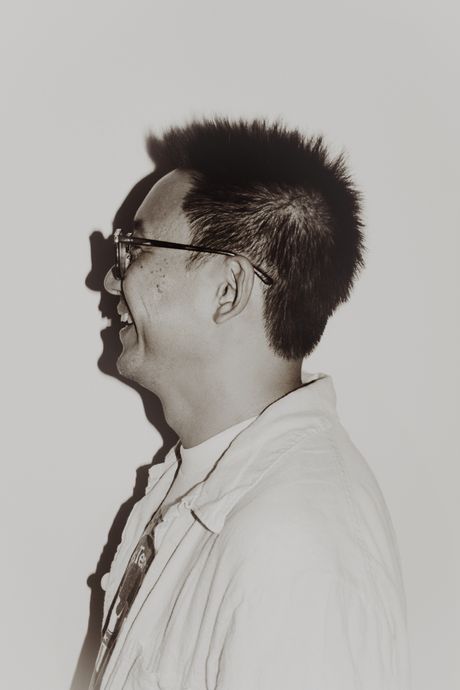

In person, Hsu exudes the same casual confidence that animates his work, speaking in finely constructed paragraphs.

He is 45 years old yet ageless in the way that middle-aged Asian men can sometimes be.

We drove to a record store in Red Hook, where once again everyone knew who he was.

(Your books coming out in September?

We should have a party!)

My parents are great, Hsu tells a therapist in the book.

My parents grew younger in Taiwan, he writes of their regular visits to the homeland.

The humidity and food turned them into different people.

This glimpse of their true selves underscored that in Taiwan he was a stranger.

Ken was popular and handsome.

He liked Dave Matthews Band.

Ken also had depths that surprised Hsu.

He inhaled the tapes Hsu made him.

Hsus obsessions amounted to a kind of code.

They were both flourishing.

Ken wanted to go to law school and tried to start a club called the Multicultural Student Alliance.

Hsu got into underground rap and fell in love.

Hsu was already a writer, but Kens murder gave him a person to writefor.

He went to Harvard for grad school, then got a job teaching literature at Vassar.

(He will begin a new position at Bard this fall.)

He started freelancing forThe New Yorkerin 2014 and became a staff writer in 2017.

Hsu does not considerStay Truea departure from his body of work as a critic.

The initial responses from friends and family were not great.

This is just getting too depressing, his wife said of his account of Kens death.

At Berkeley, he volunteered to tutor Southeast Asian middle schoolers.

It was a category capacious enough for all of our hopes and energies.

It isnt really about them being Korean American at all, he said.

They just happened to be Korean American.

I mean, look, Im not trying to die on that hill, he said, laughing.

I think thats definitely how I would generally feel.

Interestingly,Stay Truepresents Kens death as a freak occurrence with few if any racial implications.

When one editor atHardboiledsuggested looking into Kens death as a possible hate crime, Hsu bristled.

I was unwilling to relinquish him to some greater cause.

Its ironic, he conceded.

I think, in that moment, I didnt want him to turn into some symbol.

But clearly he did represent certain things to us, and he does in the book too.

Was Bejar kind of basic?

Yeah, he was, actually.

Was I …uncool?

Yes, decidedly so.

But it also means being true to yourself, and that is a trickier concept.

Is the self an innate entity your essence, your soul?

Is it contained in your roots, trailing all the way back to the motherland?

Or is it created the way a book is made by its author?

My guess is that, behind the cameras great eye, Ken is grinning.