Kate Beaton defined the late-aughts aesthetic online.

Her memoir is a monumental synthesis of history, politics, and herself.

Save this article to read it later.

Find this story in your accountsSaved for Latersection.

She spent a lot of hours alone here amid artifacts, much of them her familys.

There is a cane, the oldest thing in the museum, that belonged to a many-greats-grandfather.

Upstairs there are generations of school projects, including her own.

I spot Beatons first book on a shelf downstairs:Hark!

A Vagrant, a collection of her strange, charming webcomics.

The online comic Hark!

A Vagrantestablished Beaton as a defining voice of online humor in the late aughts.

Leaping betweenNancy Drew,Ida B. Wells,mermaids,Kennedys,St.

At its height in the early 2010s, Beatons homepage for Hark!

A Vagrantwas getting half a million visitors a month.

Her work clean, expressive, hand-drawn black-and-white comics was reblogged and reposted endlessly.

When I ask her to clarify, Hanawalt laughs.

I dont want to name names, she says.

A lot of people mimic the way she draws faces.

Ducksis a fuller expression of who Beaton is and has always been.

That book is a masterwork, cartoonist Lynda Barry tells me.

Theres nobody like her.

I need to tell you this, says Beatons 21-year-old self in the opening pages ofDucks.

I grew up listening to songs about leaving home, going to work, missing home, Beaton says.

Storytelling is a big part of the culture.

Everyone has a long memory.

Beatons own memory is a collection of stories that dont make much sense as single anecdotes.

But in Cape Breton, every recollection is tied to something else.

I think that the fact that everyone is connected, it helps us remember, Beaton says.

The threads are easy to knit together.

Its the way much of Hark!

Her 3-year-old daughter, Mary, pulls on boots to go let out the chickens.

One-year-old Charlie cant quite walk yet and cruises around their small kid-cluttered farmhouse beaming broadly.

Her given name is Kathryn, professionally she is Kate Beaton, and at home she is Katie.

(This becomes confusing when one of the cousins we run into is also named Katie Beaton.)

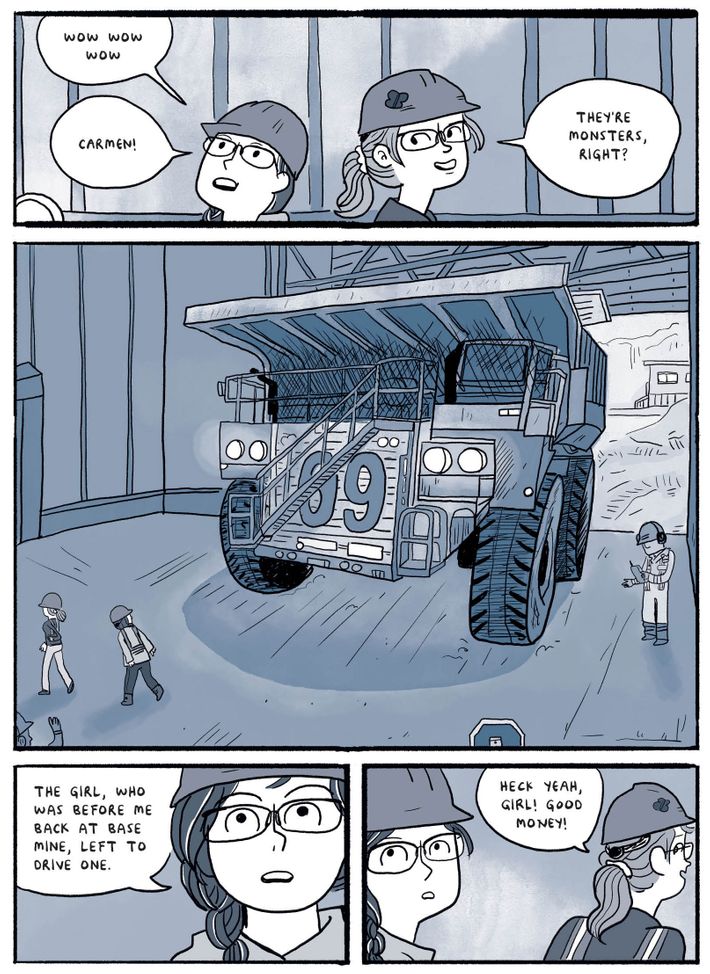

Back then, the primary hope for economic opportunity was the Alberta oil sands.

Instead, she pursued Hark!

A Vagrantcollection was published as a book in 2011, and her work appeared in MarvelsStrange Tales.

By 2015, Vulture hadpublished a Beaton interviewwith a headline dubbing her a Superstar Cartoonist.

Then a few things happened in quick succession.

In 2014, Beaton posted a long comic to the Hark!

It sparked intense national interest in the environmental impact of the oil sands.

It doesnt make the news.

Few people pay much attention.

Beaton had moved to Toronto by the time that first version ofDucksappeared, still working on Hark!

A Vagrantand a childrens-book contract for Scholastic.

In 2015,her eldest sister, Becky, was diagnosed with cervical cancer.

The short, dizzy lightness of the webcomic no longer felt like a world Beaton could comfortably inhabit.

In 2016, the year afterThePrincess and the Ponywas published, she pitched a book version ofDucks.

Becky died in May 2018.

By July, Beaton began to draw the book version ofDucks.

The first pages were rough looking and needed to be done over again, she says.

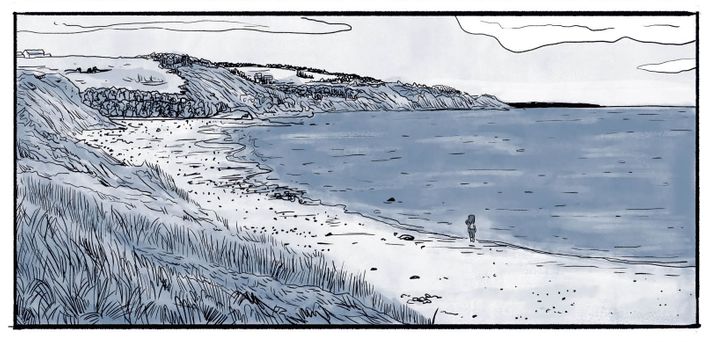

We are sitting at a picnic table overlooking Mabou Beach, a landscape I recognize immediately fromDucks.

Its like saying that I went to the moon and it was terrible.

I had a terrible time on the moon.

Theres so much I had to leave out, she says.

I kept bringing back more stories, more stories.

I wanted to be honest.

I wanted to be fair, she says.

The book runs chronologically, beginning with her departure from Cape Breton and ending when she leaves the camps.

There are endless safety training sessions in the camps, completely useless and often darkly funny.

There are many scenes of shivering in the cold, some of Beatons most intense memories.

There is perpetual, inescapable harassment.

I had to put it in the book because if I didnt, it would be a lie.

It wouldve taken out the thing that has affected me the most, for the longest time.

So it had to go in there.

Pulling one anecdote out of the entire work inevitably distorts it.

How did she do that?

She doesnt want to make claims about what other people experienced.

But she has such immense empathy for those shes depicting, even the ones it seems she should loathe.

Like something I pulled out of a hat.

Like what I did on reflection after my time there was discover that I cared, she says.

I lived with these people.

Theyre on my Facebook.

I see pictures of their family.

Not that people havent made good lives for themselves in these places, she writes.

Opinions on this are not a monolith.

Its not an effort to mitigate what she believes or to soften it or draw definitive conclusions.

People want answers for why people are shitty, she says.

I dont have that.

Nor does she have an easy explanation for whatDucksis.

There is no black-and-white for me.

Just these imprints of the things that left the biggest marks on me myself and the people I met.