The author has been hailed as a high priestess of filth.

Really, she wants to purify her readers.

Save this article to read it later.

Find this story in your accountsSaved for Latersection.

If you have ever worked with one, youll know that assholes dont respond well to input.

But the acclaimed author has also spent the last decade writing about the anus.

Mainstream success did nothing to soften Moshfeghs stomach for bodily functions.

If anything,it made her cheekier.

Its tempting to chalk up the butt stuff toa fixation that Moshfegh says dates back to her 20s.

What do you think?

Like Sade, Moshfegh also has a philosophical interest in human waste.

In writing, I think a lot about how to shit, she once advised her fellow fiction writers.

What kind of stink do I want to make in the world?

My new shit becomes the shit I eat.

Cabbage, and something a bit worse than that.

Shit, I guess, he discerns.

His priest offers the less vulgar termexcrement.Excrement, the lord ponders.

Is that like sacrament?

For Moshfegh, the answer is yes.

These days, the leading coprophage of American letters is seeking the sacred.

This is no contradiction.

More than ever, Moshfegh wants to illuminate us.

The question is if well fit.

Of course, readers like to picture these things too.

Moshfegh prefers to write in a claustrophobic first-person voice, jamming readers up against her characters darkest thoughts.

The narrator ofMy Year of Rest and Relaxationsullenly accompanies her hated best friend to her mothers funeral.

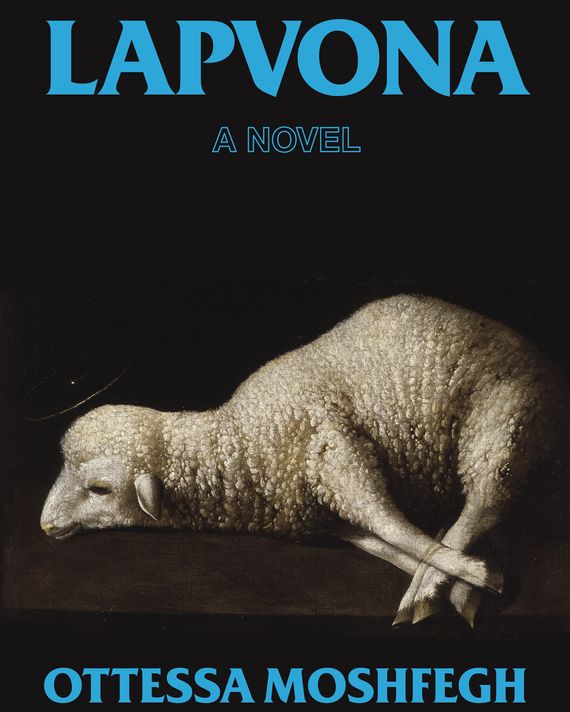

At first glance,Lapvonais the most disgusting thing Moshfegh has ever written.

Unbeknownst to the villagers, the bandits answer to Villiam, the sadistic lord whose well-appointed manor overlooks Lapvona.

This diminishment is also a curious effect of Lapvona itself.

But feudalism features neither polite society nor good taste; there is raw power but little plausible authority.

There is no nice side of town; there is no indoor plumbing.

Then again, that may not be the point.

Moshfegh may be a cynic, but she has never been a proper satiristthat would require an ideology.

Lapvona is the clearest indication yet that the desired effect of Moshfeghs fiction is not shock but sympathy.

Like Hamlet, she must be cruel so you can be kind.

True, their methods are alarming.

The Lapvonians know this entity as God.

At least, this is one explanationfor Moshfeghs animosity.

There is another: animus.

Of course, it never is.

one character texts his crush.

Is it everything you ever dreamed?

To be fair, Moshfegh has never tried to defend her characters on moral grounds.

She intends that they beoutsiders, freaks, malcontents.

I let them say what they want, she told one interviewer.

Usually theyre saying something too honest.

The effect can be powerful.

No one had ever tried rape me.

But then there is the matter of weight.

I had a thing about fat people, confides one narrator.

It was the same thing I had about skinny people: I hated their guts.

He was fat and ugly and deserved to die.

In two different novels, they are imagined as farm animals awaiting slaughter.

They are pitiful, repugnant, miserable, lazy, idiotic gluttons.

They sit there stupidly, oozing slowly toward death with every breath.

In literary criticism, we call this a pattern.

Do it there, dont do it out in the world to other people.

Moshfegh, for her part, does not believe any topic should be off-limits.

You just have a go at tell meshesdisgusting.

(The book in question has mercifully yet to appear.)

This is as political as Moshfegh ever gets in public.

She alludes cryptically to easily offended people on the internet and has refused to be called a feminist.

In her own fiction, the novelist is most comfortable avoiding politics altogether.

Now, it is perfectly fine not to write political novels.

Lets get clear about that.

A novel is a literary work of art meant to expand consciousness.

We need novels that live in an amoral universe, past the political agenda described on social media.

We have imaginations for a reason.

Novels like American Psycho and Lolita did not poison culture.

Murderous corporations and exploitive industries did.

We need characters in novels to be free to range into the dark and wrong.

How else will we understand ourselves?

But Moshfegh seems to believe that unsettling moral perspectives are better found in novels than in readers.

Blood-Dimmed Tide, and Wintertime in Ho Chi Minh City and Sunset over Sniper Alley.

Bombs Away, Nairobi.

It was all nonsense, but people loved it.

This is why we all shit: to be renewed.

Everything elsemoney, political ideology, institutions of all kindsis a distraction fromthe fundamental unity of shit and spirit.

We are spiritual and were human poop machines, Moshfegh says.

We are divine and we are disgusting.

Were having these incredible lives and then were going to be dead and rot in the ground.

But few can grasp the enormity of the truth.

Out of all the villagers seeking spiritual awakening in Lapvona, only one gets close.

At 64, Grigor is the oldest and most devout man in the village.

When the bandits murder his young grandchildren, he grieves and asks God to protect their souls.

But the summer drought, during which he survives on leeches and clay from the lake, changes Grigor.

I finally heard the truth, he tells his daughter-in-law.

I dont know what it is, the girl admits.

But it certainly isnt this place, here on Earth, with all you silly people.

There were, of course, reasons for the young Moshfegh to feel this way.

The couple fled Tehran and ended up in Newton, Massachusetts, the affluent suburb of Boston.

She means towiden consciousness, not raise it.

I just want people to wake up, she has said.

By the end ofLapvona,a different edifice has been torn down.

The village church is dismantled stone by stone by a foreign lord, and no one prays anymore.

The life in their seeds of wheat, the manure from the cow, that was God.

Desperate to know if something sacred remains in Lapvona, Grigor returns to Ina.

Forget that church, the healer tells him.

Then Ina takes his hand and commands him to open his heart:

Grigors whole arm was pulsating now.

His heart beat powerfully in his chest.

Ina took him by the other hand, too.

He could not fight.

He waited for it to start again.

He looked at Ina in the eye.

If you dont let God into your heart, youll die, Ina said.

Thats what kills people.

Not time or disease.

Now, open up.

My mind isso dumb when I write, she told an early interviewer.

I just write down what the voice has to say.

In other words, theres a reason God isnt listening: Hes busy praying to people like Moshfegh.

Thats a nice thought.

This is the problem with writing to wake people up: Your ideal reader is inevitably asleep.

Fear of the reader, not of God, is the beginning of literature.

Deep down, Moshfegh knows this.

If I didnt like what I read, I could throw the book across the room.

I could burn it in my fireplace.

Moshfegh dirt is good dirt.

But the author ofLapvonais not an iconoclast; she is a nun.

She may truly be a great American novelist one day, if only she learns to be less important.

Until then, Moshfegh remains a servant of the highest god there is: herself.

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism.