Save this article to read it later.

Find this story in your accountsSaved for Latersection.

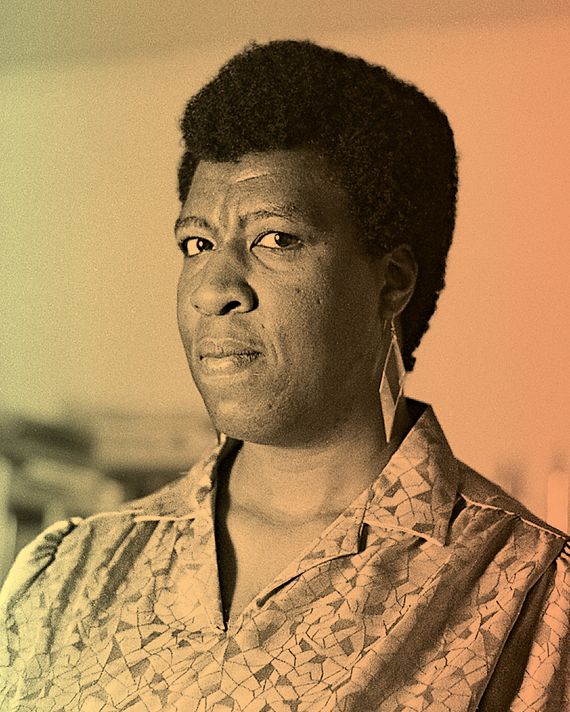

Her grandmother was an astonishing woman.

There was no school for Black children, but Estella taught Octavia Margaret enough to read and write.

Her father, Laurice James Butler, worked as a shoeshiner and died when she was 3 years old.

Octavia Margarets dream was to have her own place where she could tend her garden.

OctaviaButler,asunderstoodby…

.Her spectacular life.

Her most misunderstood work.

Her writing style.

Her famous journal entry.

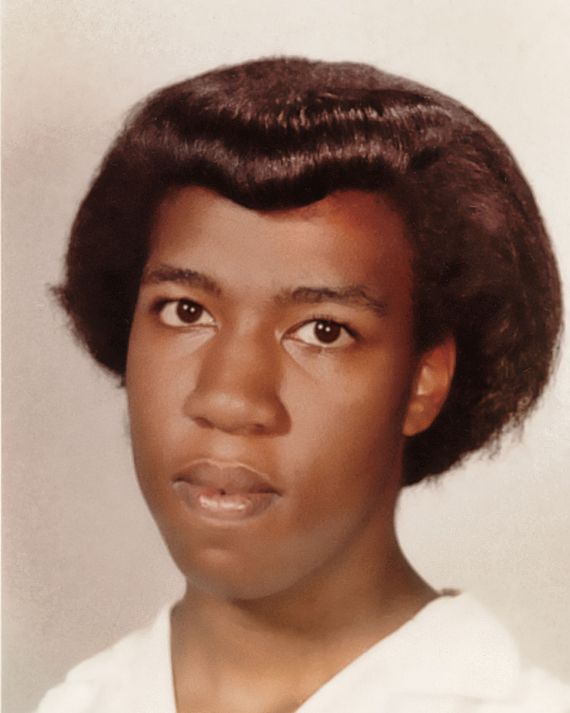

As a girl, she was shy.

She broke down in tears when she had to speak in front of the class.

Her youth was filled with drudgery and torment.

I wanted to disappear, she said.

Instead, I grew six feet tall.

She was called slurs.

It was the only time in her life she really considered suicide.

She kept her own company.

In her elementary-school progress reports, one teacher wrote that she dreams a lot and has poor concentration.

I usually had very few friends, and I was lonely, Butler said.

But when I wrote, I wasnt.

By the time she was 10, she was writing her own worlds.

At first, they were inspired by animals.

Childrens capacity for cruelty stayed with her.

She found a refuge at the Pasadena Public Library, where she leaped into science fiction.

She was a comic-book nerd: first DC and then Marvel.

I needed my fantasies to shield me from the world.

When she learned she could make a living doing this, she never let the thought go.

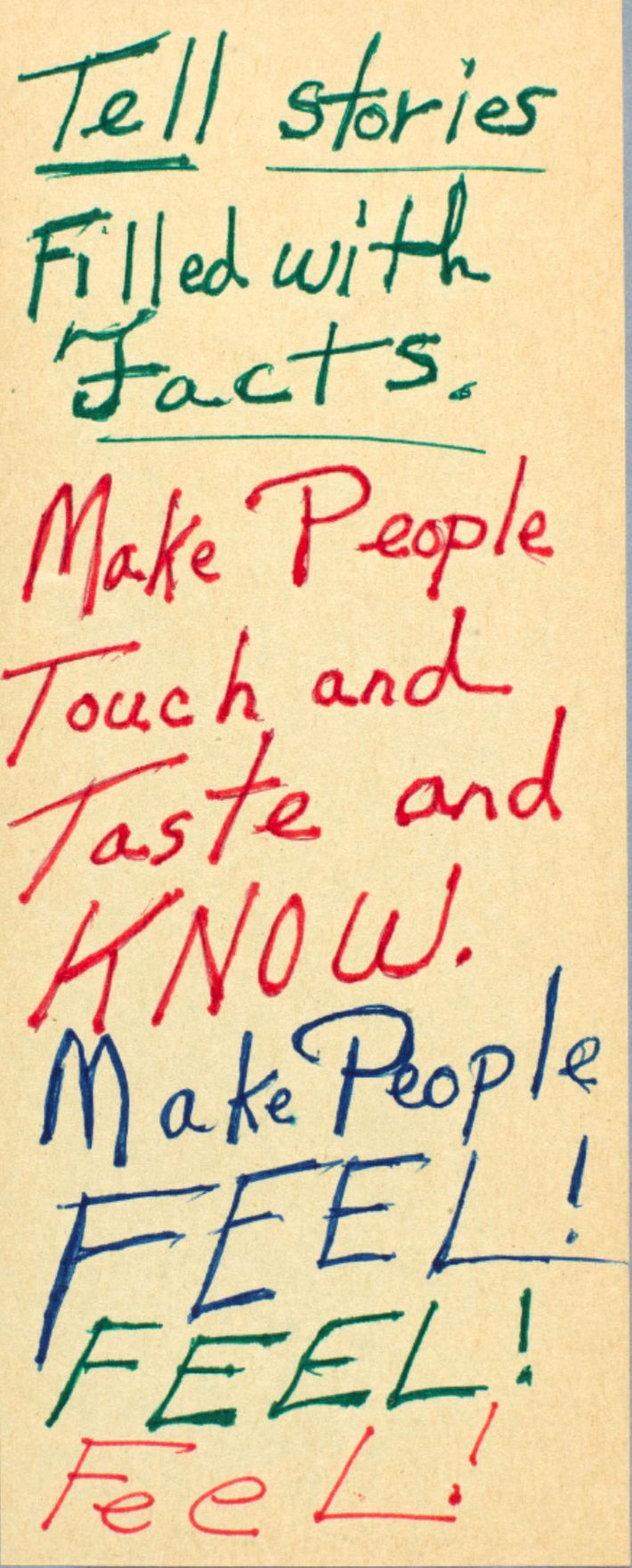

Later, she would call it her positive obsession and would put it all on the line.

Despite her familys warnings, she did exactly what she wanted to do.

My aunt was too late with it, though, Butler said.

She had already taught me the only lesson I was willing to learn from her.

I did as she had done and ignored what she said.

Butler would grow up to write and publish a dozen novels and a collection of short stories.

She did not believe in talent as much as hard work.

Persistence was the lesson she received from her mother, her grandmother, and her aunt.

The world would catch up to her dreams.

She is now experiencing a canonization that had only just begun in the last decade of her life.

As a female and as an African-American, I wrote myself into the world.

I wrote myself into the present, the future, and the past.

Her characters were brazen when she felt timid, leaders when she felt she lacked charisma.

They were blueprints for her own existence.

I can write about ideal mes, she wrote on the cusp of turning 29.

I can write about the women I wish I was or the women I sometimes feel like.

I dont think Ive ever written about the woman I am though.

That is the woman I read and write to get away from.

She has become a victim.

She is a victim of herself.

She must climb out of herself and make her fate.

How can she do this?

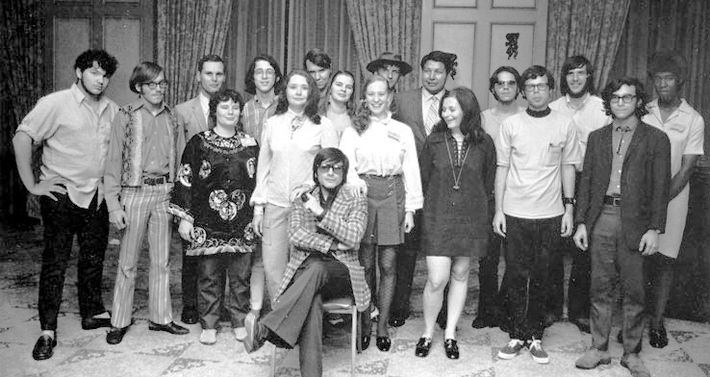

Butler was onthe 6 p.m. Greyhound bus in Pittsburgh heading home from the Clarion Workshop for science-fiction writers.

She felt proud of the past six weeks.

She had just turned 23, and Clarion was the first time she was taken seriously as a writer.

After graduating from high school, she had continued to live at home while attending Pasadena City College.

Clarion was the farthest Butler had ever been from home and required a three-day cross-country trip to get there.

Adjusting was difficult at first.

Western Pennsylvania was hot, humid, and lonely.

The radio stations stopped playing at eight.

When the other students socialized, she wrote letters to her friends and mother six in the first week.

(She probably shouldnt have said that, she thought later.)

When she felt particularly hard on herself, she would write letters to her mother she never sent.

Im not doing anything, she wrote.

Im hiding in this blasted room crying to you.

Her mother had forgone dental work so Butler could attend.

She wouldnt complain like that.

Yes, she was still shy.

She rarely spoke in class, and when she did, she put her hand over her mouth.

But Ellisons session was a shot in the arm.

Butler hadnt turned in anything all workshop, and his one-story-a-day gauntlet invigorated her.

Ellison was a social force: vexing and impossible to feel neutral toward.

He would tell Butler to Write Black!

and Write the ghetto the way you see it!

advice that annoyed her.

She also had a crush on him.

Llano could easily be that master, she wrote.

But she was wary of losing herself.

If I am not careful, he will take over without even realizing it.

A master must teach me to use my own talent, not to lean on his.

I love him, but this is not what he teaches.

So I will continue to love him and teach myself.

The high of Clarionwore off quickly.

Ellison had promised Childfinder would make Butler a star, but the publication ofThe Last Dangerous Visionskept getting delayed.

She sent fragments ofPsychogenesisto Diane Cleaver, the Doubleday editor she met at the workshop.

Cleaver said it was promising but she would need the complete manuscript.

Over the next five years, Butler didnt sell any writing but wrote constantly.

On Saturdays, she packed a draft ofPsychogenesisinto her briefcase and went to the library to do research.

She tried to stick to a tight schedule.

Every morning at 2 a.m., she woke up to write.

Sunrise brought the life she did not ask for: menial jobs at factories, offices, and warehouses.

She subsisted on work from a blue-collar temp agency she called the Slave Market.

Her body hurt; she needed to go to the dentist.

She took NoDoz to stay awake during the day.

She believed in its real-world utility, too.

She would learn to manifest.

You had to do it with faith.

For a stretch of months in 1970, Butler would follow these instructions in the morning and at night.

Goal: To own, free and clear, $100,000 in cash savings, she wrote.

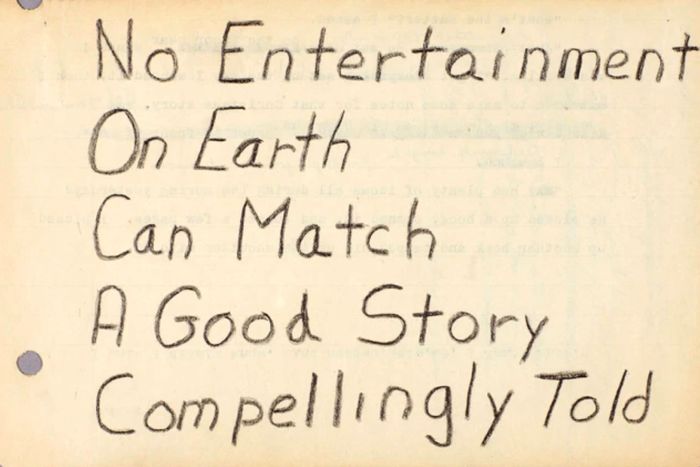

Writing was an incantation, a spell she could cast upon herself and the reader.

The goal right now is to achieve a scene of pure emotion, she wrote.

Then, in December 1975, at 28, she sold her first book.

After losing thePsychogenesisdraft, she began writing another novel,Patternmaster,that takes place in the same universe.

Butler sent the manuscript to Doubleday.

By then, Cleaver had left, and Sharon Jarvis, the science-fiction editor, accepted the submission.

The novels poured out of Butler during this time.

In other words, she wrote about characters she aspired to become.

InPatternmaster,the two characters are upstaged repeatedly by Amber, a healer neither can control.

By 1977, Butler had two published novels but was no closer to financial security.

Jarvis had given her a $1,750 advance forPatternmaster,which was not enough to live on.

Their editor-writer relationship was workmanlike.

What is it you want of Sharon Jarvis?

Then we both played at not knowing why she was behaving that way.

(Jarvis recalled this, too.

When I was an editor, I didnt give a crap about somebodys background, she said.)

AlthoughMind of My Mindwas accepted for publication, Jarvis said there was a catch.

Even the use of Christ as an expletive must go.

(The N-word, however, was published without concern.)

Butler had been intentional about cuss words, even outlining which ones each character would use.

(The character Karl, for instance, would stick to religious outbursts like Hell!)

She felt the changes made the dialogue stilted and untrue.

I dont think the story suffers in any way if you change it, Jarvis responded.

Consider Barry Malzbergs words: If its money versus integrity, money wins out every time.

(Jarvis said the maximum amount she could offer any author at the time was $3,000.)

Is that finally clear?

Butlers relationship with Doubleday continued to deteriorate.

In general, there was little to no effort to promote her books beyond the library presales.

Take it all in stride, Jarvis replied when she asked her about these issues.

I cant pretend to be happy about that.

I accept your offer of $1,750, but Im not happy.

Butler would haveto promote herself.

She sentPatternmastertoMs.Magazine for review consideration.

She regularly attended science-fiction conventions like Westercon to data pipe and sell books.

How do we win?

Perhaps because of Butlers efforts, her books sold better than Doubleday had expected.

Jarvis told herMind of My Mindwent into a second printing because we underestimated the advance sales.

(Ignorance is expensive, Butler would later write.)

Writing a best seller was a constant preoccupation a way to make life financially sustainable.

I need something that sells itself, she wrote.

Something that screams its significance or its scariness or its timeliness so loudly that it cant be ignored.

Her next book would be her first stand-alone novel.

When she believes her own life to be threatened, she returns home.

Early in her career, Butler received criticism for not writing explicitly about racial politics.

Why do you write that stuff?

she recalled being asked.

You should write something thats more politically relevant to the struggle.

She first got the idea forKindredin college when she was a member of the Black Student Union.

His impertinence reminded her of herself when she was younger.

One day, she told her mother, I will never do whatyoudo.

Normally, her mother would have put her in her place, but that day she didnt say anything.

She just gave her daughter a quiet look.

A proud Black man like him who would look a white man dead in the eye?

He wouldnt last long enough to learn the rules of submission.

I was wild forKindred, said Eth.

It was a real departure from what people were writing or reading about.

Most editors resisted the genre mixing.

The blend of realism and fantasy just didnt work to my mind, replied Daphne Abeel at Houghton Mifflin.

I have that faith and dont want to give up.

The book was published in 1979 and received a muted response.

But a couple of experiences helped with that.

Moreover, she began to feel she was owed money commensurate with her work.

I will be sold cheap as long as I permit myself to be sold cheap, she wrote.

I will not permit it again.

When she was younger and less confident, she often reprimanded herself for saying something she thought was embarrassing.

She wanted to become unembarrassable but later understood she needed to let go of that.

I maintain distance between myself and other people out of fear.

Fear of the pain they will give me if they see me naked.

And find me not merely ugly, but foolish and without value, she wrote.

The defense is not to care.

Loneliness was a constant affliction.

She wanted companionship and sex.

Another person would help me to grow up socially, she wrote.

A lasting relationship would be good for me.

Often, she imagined being with a man: We want now a man over six feet tall.

White, Black, yellow, we do not care.

During her late 20s, she also imagined herself with a woman.

I know that but for the social stigma, I would rather love women, she wrote.

I do it so easily.

Closeness with men doesnt seem to fulfill except physically.

When Butler was 28, she decided to stop living inside her head and meet some women.

She worried most about how being in a relationship with a woman could impact her career.

Isnt being Black and female stigma enough?

It could hurt me.

However small I am, it could.

If I keep low after coming out, is it fear or shame?

Not that I dont share their unifying inclination.

Why am I being so oblique today?

Her journal from the first meetup burns with an intensity of detail.

She noticed that all of them were white.

She watched them kiss one another in a way she knew wasnt sisterly and felt pangs of envy.

(Then she worried about coming off as a killjoy and know-it-all.)

Butler ended the day in a heap of anguish.

If only she had a friend to guide her.

At another meeting later in the month, she decided she was done.

She sat through the centers announcements and went home.

I dont belong there any more than I belong anywhere else, she wrote.

It would require an effort that Im not willing to put forth to make me part of those people.

Theyre not for me.

If I found a woman I went well with, we could make it.

As far as her close friends and editors knew, Butler wasnt in a romantic partnership.

I am sorry that she did not seem to have that deep, intimate relationship, said Barnes.

It can be difficult for artists.

She had that sense of existential loneliness that human beings get.

It was a price she was willing to pay to become the human being that she wanted to be.

She became that person, and all it takes to get everything you want is everything youve got.

Butler never learnedto drive.

She observed people and occasionally wrote character sketches.

(It would go unpublished.)

Butlers Uncle Clarence had recently died, and another friend attempted suicide.

She worried about her safety and told Barnes she wanted to take martial-arts classes.

The main thing I felt was wronged, she wrote after one burglary.

I thought,Why did they do it?I had so little.

Meanwhile, she felt the world was in a state of regression.

Butler was a self-professed news junkie with a keen interest in political leaders going back to the Nixon-Kennedy debates.

She wanted to understand how their words held sway over people.

Bigotry is easing back into fashion, she wrote shortly after the presidential election of Ronald Reagan.

His attack on social-welfare programs and environmental regulations and the funny math of Reaganomics all filled her with dread.

She sent her mother some money and bought herself a plane ticket to Peru to location-scout for the books.

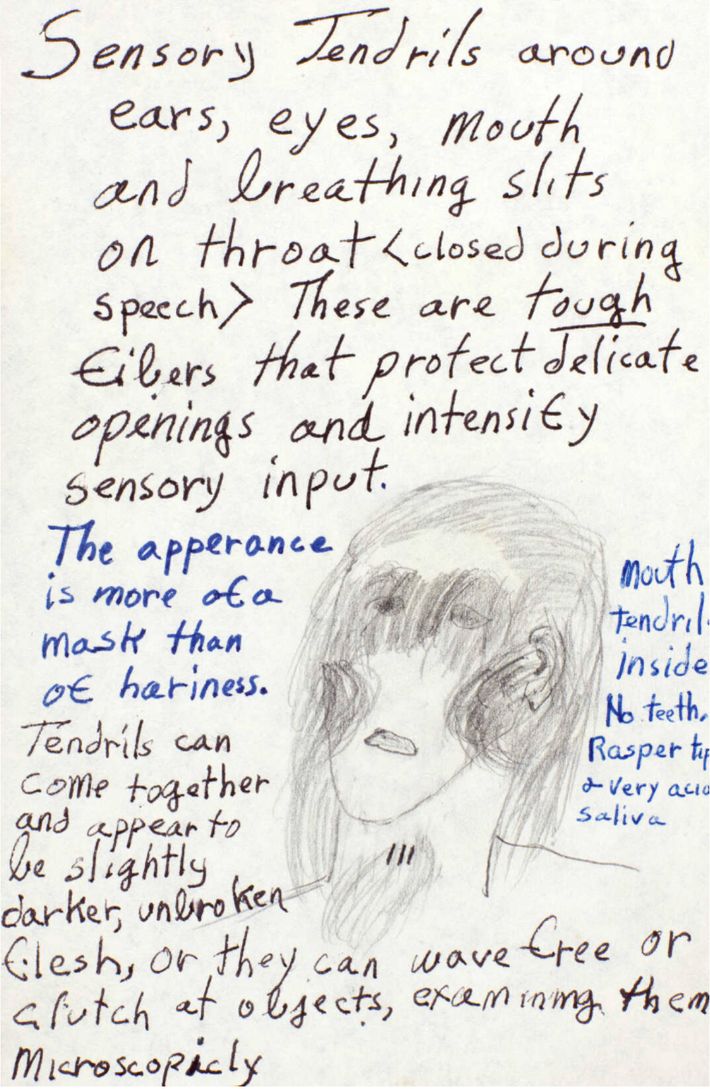

The Oankali tell Lilith humanity is doomed because of two incompatible characteristics: intelligence and a hierarchical nature.

While humans are xenophobic, these aliens are xenophilic.

Essentially, evolve or die.

Butlers dire prognosisfor the world brought her acclaim.

That Christmas, she paid off the mortgage on her mothers house.

Butler was in her 40s now.

In a way, I have run dry, she wrote in a moment of discouragement.

You start to repeat yourself or you write from research and/or formula.

What if she were to graft this idea onto space-colonization narratives?

Wouldnt a planet reject humans like a body rejecting an organ transplant?

This could be a series exploring different worlds and their peculiar challenges.

Thats what I feel like doing.

You see, this is what Im like when Im in love.

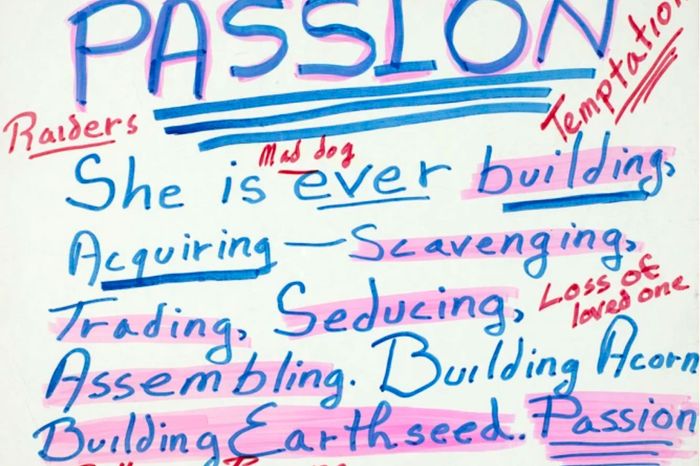

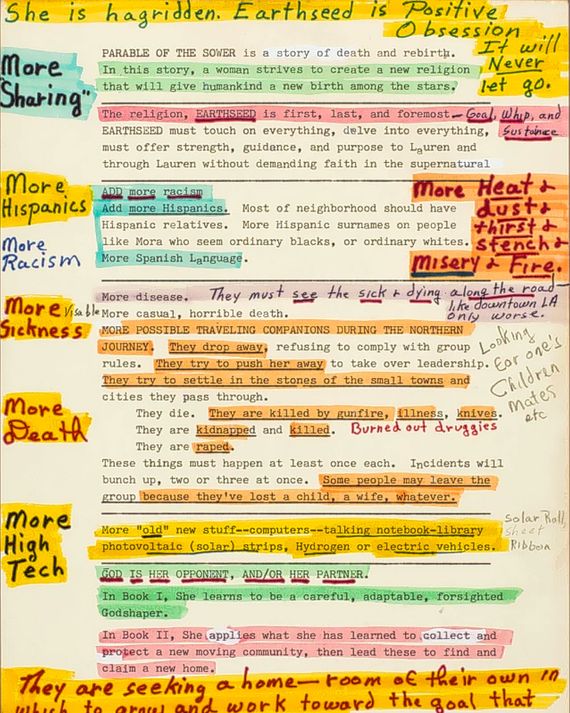

The resulting book,Parable of the Sower,begins in Southern California in the year 2024.

Earth, ravaged by the climate crisis called the Apocalypse, or the Pox, is beyond repair.

People have become chained to systems of indentured servitude by company-owned cities.

She knows this safety is an illusion and records her beliefs secretly in a notebook.

She suffers from a hyperempathy disorder, a crippling condition that causes her to feel what others feel.

It forces her to be a tougher, faster decision-maker.

She becomes the magnetic leader of a new religion but works slowly and subtly through actions and common sense.

Over four years, Butler rewrote the first 75 pages several times.

Everything I wrote seemed like garbage, she said.

Poetry finally broke the block.

I was forced to pay attention word by word, line by line, she said.

She advocates for adaptability and communality as the path of survival for the species.

One of the first poems I wrote sounded like a nursery rhyme.

It begins: God is power, and goes on to: God is malleable.

This concept gave me what I needed, she wrote.

Space colonization was Butlers equivalent to building a cathedral.

She believed only some extraordinary feat like space travel could bring people together in a common goal.

Earthseed doesnt just reconcile science fiction and religion, wrote her biographer Gerry Canavan.

It remakes science fictionasreligion.

Parable of the Sowerwas published in 1993.

She spoke at independent Black-owned, science-fiction, and feminist bookstores.

For the first time, the New YorkTimesreviewed her work (albeit as part of a science-fiction roundup).

The greater culture was shifting to meet her.

On June 9, 1995, Butler received an unexpected call.

She was so surprised that she didnt ask about the particulars.

In her journals, she gave the award a code name: U.B., for Uncle Boisie, a.k.a.

Guy, possibly as a reference to a male academic who had nominated her.

This isnt real yet, she wrote.

It wont be until the letter arrives.

What am I to do?

Let us consider sensible behavior.

She would enroll in the foundations health plan.

She would get life insurance and add her mother as its recipient.

It would be the largest sum of money she received in her lifetime.

The letter read:

Your award carries with it no obligations to the Foundation of any kind.

Quite simply, your award is for you to use for whatever purposes you choose.

1996, $57,500.

1997, $58,500.

1999, $59,500.

A chance to writeandto meet daughterly obligations, she wrote.

A year later, her mother had a stroke and was hospitalized for three weeks before dying.

Butler rarely spoke about the death publicly or with friends.

I wrote nothing of value for some time, she said.

Her grief focused her as well.

Butler would say this was my mothers last gift to me.

In addition to the financial stability, the MacArthur grew her stature.

That year, Butler also received a PEN Lifetime Achievement Award.

Her goal of $100,000 in savings had changed to $1,000,000.

True to its name,Parable of the Tricksterconfounded her.

Butler wrote dozens of fragments that never moved beyond exposition.

Republicans continued to depress her, particularly George W. Bushs invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan.

She needed a break, so she started writingFledgling,a sexy polyamorous vampire novel, instead.

But writing had become generally difficult.

Beginning in the late 90s, Butler began to feel fatigued.

She kept notes of her symptoms shortness of breath, nausea, back pain, hair loss.

Her condition continued to deteriorate into the new millennium.

She got pneumonia that was misdiagnosed and left untreated for weeks.

Soon, she couldnt walk more than half a block without getting tired.

Im not functioning, she wrote in 2004.

I sit and drowse a lot.

I know Im not thinking very well, and Im certainly not breathing very well.

Howle remembers her then: young and mosquito bitten and grinning after her trip to Peru.

She really loved getting out in nature, said Howle.

If Octavia had a place where she saw God, that was it.

She had fallen outside of her home, hitting her head on the concrete.

She was 58 years old.

Up until then, the medical advice she had received was to exercise more.

And shed be like, Oh, do you want me to wait for you?

What happened with Octavia didnt need to happen, Howle continued.

Despite being the incredibly powerful person she was, she did not assert herself with her doctor.

Even today, doctors discount women of a certain age and women of color.

She needed more people who were protective of her.

Howle remembered the way Butler would end calls by saying, Ill be seeing you, then.

Butlers name has only continued to grow.

Since 2004, when BookScan began tracking numbers, over 1.5 million copies of her books have been sold.

In 2021, NASA named the landing site of the Mars RoverPerseverancethe Octavia E. Butler Landing Site.

His is the first out of the gate.

Her most lasting legacy, though, is her writing, published and unpublished.

She kept the correspondence she received and made copies of the letters she sent just in case.

She saved everything except the rejection slips she threw out in a fit of despair when she was young.

Today, her writing is often read inspirationally and aspirationally.

Some have taken the tenets of Earthseed literally as a philosophy of living.

Octavia Butler knew is a common response to cataclysm.

She wasnt sure imperfect people could ever create a perfect world, but they could try.

What the archives show is how much she struggled with hope herself.

She was a pessimist if Im not careful.

When she was working on a novel, her drafts tended to reveal the crueler sides of human nature.

She didnt like Lauren Olamina at first because she saw the character as a power seeker.

You could understand this as a function of her desire for commercial success: We all need heroes.

But another way to see it is that hope is not a given.

Hope and writing were an entwined practice, the work of endless revision.

An earlier version of this piece incorrectly stated theKindredseries will be coming to FX.

It will air on Hulu.

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism.